“Fantasy—the unrestrained flow of imagination—is closer to delirium. Creativity, on the contrary, requires concentration, bringing ideas together into a coherent mechanism.” —Ricardo Bofill

Much has been said about the connection of writing and architecture.

In both, organizations of relations, feelings, experiences, and gods are created, maintained. The pair, which stands at the origin of culture, is said to correspond in some way with being as two essential sides of the human reality—architecture: the objective material of our sovereignty, teamwork, exuberance; and writing: the subjective drives, radical heterogeneity, and power of isolation. That’s all fine, clean‚ even proper, but what about the present and the way things are actually used? Architecture has become a symbol for our society whereas writing has been, in all but the rarest circumstances, over bred, dragged through mouths and keyboard, torn down as base and in many ways destroyed as a pillar

Today, architects are much, much more famous than poets. It’s no surprise: the grandiosity of post-industrial capital struts in towering constructions that burst from the old modern neighborhoods like titans, towering over blasted landscapes. If the economy is the force of humanity which floats above the face of the earth, the architects is its avatar. And writing has become like rain that only the craziest and those with the most time can capture in any meaningful sense, the rest rolling into the gutter.

Ricardo Bofill, the Catalonian architect who died last week from COVID at 82, was a visionary who not only complicated the situation of contemporary architecture since his emergence in the late ‘60s but in many ways made the subjective/objective binarism of writing/architecture useless. His is an architecture of the beyond, always beyond. He embraced the poetic, conceptually and literally, in his works, and created timeless structures that burst from city block and suburb like inspirations in the night.

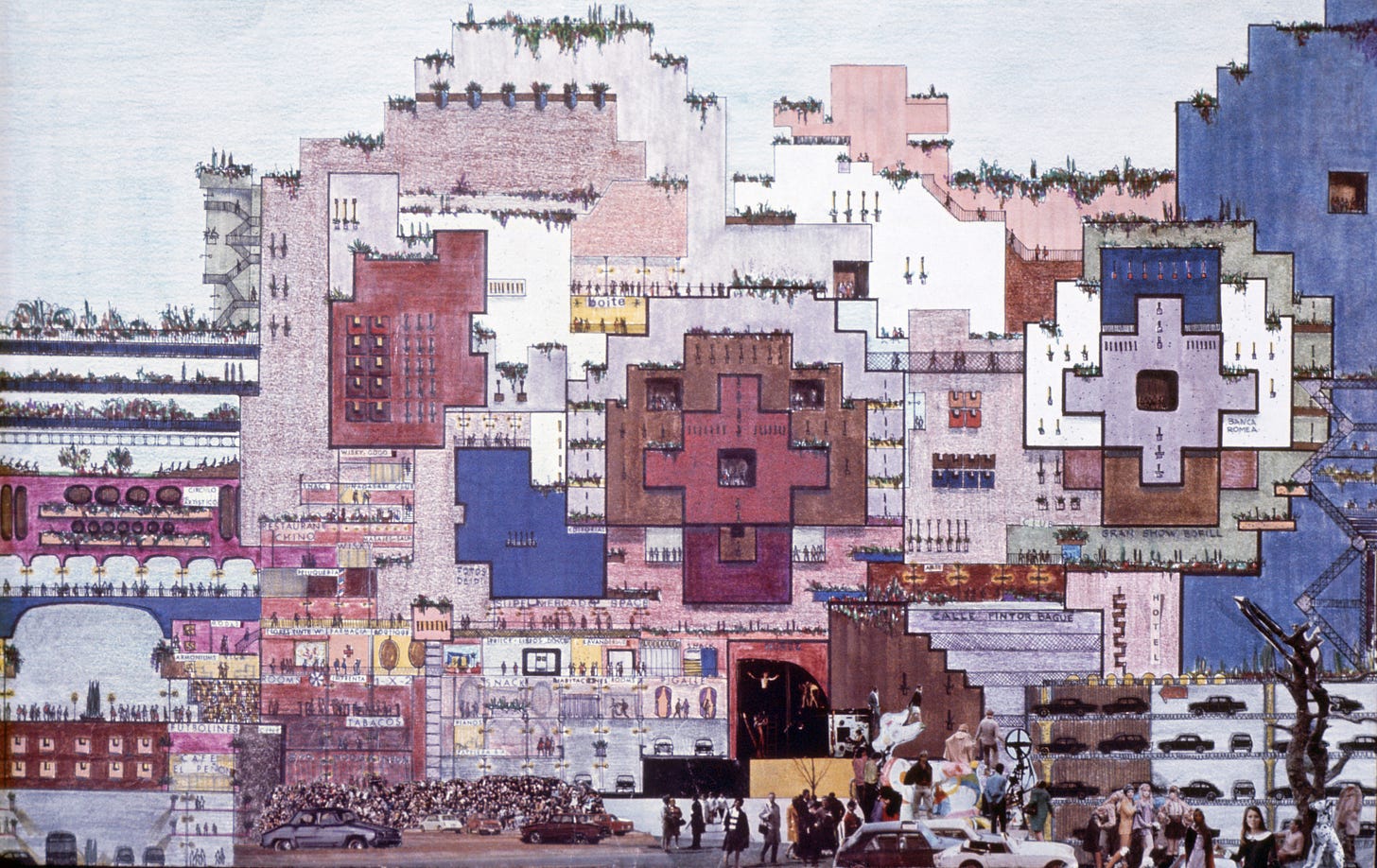

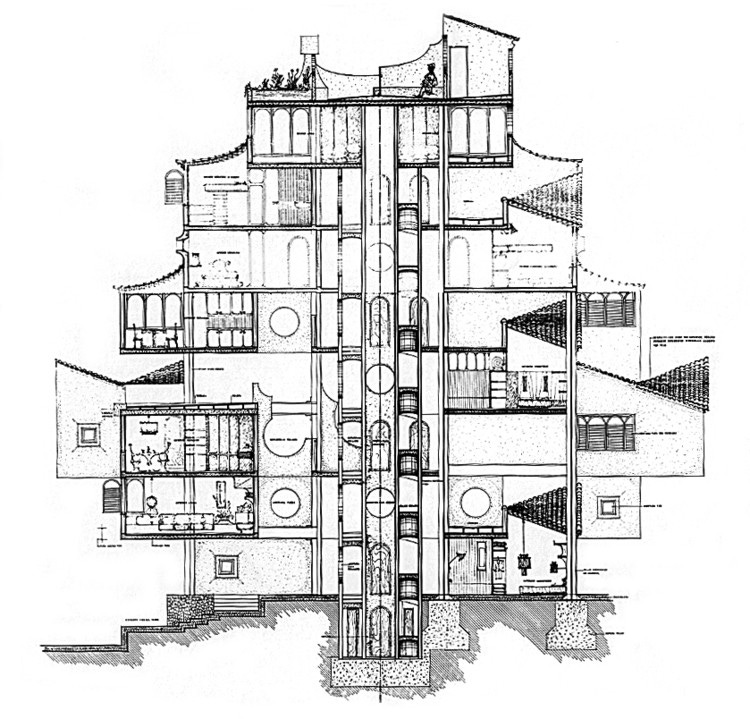

From the massive terracotta modular housing projects painted in bright colors to the modern classical housing projects and the more contemporary glass towers and terminals, Bofill’s architecture doesn’t so much act as an extension of society in the present but acts as a re-combinatory condensation of the processes of reflection, taking in all that came before, wielding time in a way that modernism never did, embracing all of the gestures and practicalities of deep history. In fact, Bofill was constantly repudiated by society in which he tried to build, first being expelled from school in Barcelona for socialist organizing under the Franco regime (what being cancelled actually is) and again in Madrid where he was expelled for a party on the plot of land where his famous The City in the Space, a ] utopian city-structure, was supposed to be sited. Bofill’s work is so singular, so drawn from the alien territory of pre-capitalist construction that the structures do seem futuristic, even alien, to many–and he was often treated like it.

Like so many greats who begin in exile or obscurity, the critics cannot get enough of him today. The opinions are many. But often when people speak on Bofill and his Taller de Arquitectura they are preoccupied with his status as one of the touchstones of postmodern architecture. This facts dominates the conversation, unfortunately. It’s a title that Bofill embraced, but, probably in order to skate cleanly through the conversation. In one of final interview he impatiently waves away the idea of categorization. Framing his project in terms of postmodernity was probably functional, a way for the public and intellectuals to understand, though who really is conceited enough to deny the keys to a movement?

The public does seem to understand Bofill—despite the failure of his utopian dreams; they even love him. Walden 7, which stands next to La Fábrica, Bofill’s famous home and headquarters, exists in the outlying industrial zones of Barcelona, far from any considerations of accumulation or social hipness, a testament to the man’s idea that cheap housing did not have to look cheap; his vision of social housing and monumentality completely rebuked the stern uniformity of Western European modern and Soviet governmental styles, while not ignoring the dramatic gestures of either.

That Bofill was able to incorporate so many different styles over time and change his whole look so constantly, without sacrificing the spirit testifies to his respect of the range of influences that living in a globalized culture allows as well as the specific cultural requirements of each building site.

In an interview with Pin Up he says:

And I tried, with a team of around 20 people, working “word by word” to learn and acquire all the different architectural languages possible. Once I’d studied Classicism, once I’d studied all these architectures, the culture and language of a building became a secondary element. And above all a non-ideological element, because — especially at that time — if you didn’t produce a certain architecture you were a reactionary. Architecture was very ideologized, aesthetics had become something ideological, but I wanted to erase all that. For example, there are great writers, like Céline, who was rather rightwing, and who was a very good writer, or those like Borges, who write in a totally formal, classic way and are very good … Personally I think one should know all the different writing styles in order to be able to use them in each particular case one sees fit in the manner one wishes.

The grammars and styles are pulled together by something unclear, nuclear. And Gravitational centers exist all throughout the world as places that revive and condense knowledge, emulating the true spirit of the city, something with pull, a site that sits beyond representation. “The great architects have forgotten the theme of the city because it’s too complicated. They’ve proven unable to take hold of it or haven’t known how…”says Bofill, who embraced the trials of highly complex times, an earnestness that attracted poets and dreams, junkies and runaways to his early projects in Spain and France. Where postmodernism always, in my mind, has a sense of academic critique, dealing with the remnants of high culture, the Taller’s work seems more dreamlike, not in a weird or uncanny sense, but in its ability to take all sorts of influence, recombine them, and give them a gravitational pull, an attraction, sometimes a fatal one, as some of the buildings are said to have become popular places at which to take the final leap.

These structures have become sites of aesthetic pilgrimage with thousands travelling yearly to use the locations as backdrops for Instagram and even major motion pictures, especially the older Spanish works of “chromatic exuberance” (Douglas Murphy), a fact that is easy to disparage and easily upsets locals, but is interesting when you think about how loci of human congregations have inexplicably come together to mark holy and important sites through time: in the mountain cities, in the religious centers desert in the desert, temples where people linger hoping to hear a whisper from the shadowy vaulted recesses.

Ritual space, calling to ritual, obelisks, spaces primordial wellness, spaces to commit crimes, spaces to dream outside of the constant call to efficiency.

In another interview, Bofill digresses into concept of monumentality, which, for him does not exist sheerly in terms bigness—the nomads had mobile monuments after all, made their communities geometric monuments to endurance in the wastes— “Monumentality begins with the ritualization of life. When life calls for ritualization, the system of monumentalization becomes a possibility. This current epoch is defined by uncertainty, a time of equivocal future. Up until the year 2000, the most well-prepared individuals were capable of making future predictions, or providing prognoses. Since the year 2000, this capacity broke. And it is in times of uncertainty that small gestures—writings, statements, concise and diverse actions—are necessary. Small monuments in a world of flux. These are, in a certain way, the only type of works that can be done today.” Small monuments. The architecture of the beyond has left the material plane and moved into books. If not something to believe in, then maybe Bofill’s architecture is more like a tomb—a dour possibility.

But a tomb that’s viewed by people that can understand is always also art. And Bofill’s monumentality-without-power led him to explore different magisterial forms: the French classical block that appear like a Vatican without any cardinals, the Romanesque glass skyscrapers in New York, the modular casbah inspired Kafka’s Castle, named for the imposing cubic face that’s almost impossible to read from the outside. If architecture is to become literary it“requires a backward activity to precede it, the unbuilding or decomposing of existing structures, either actual architecture or present conventions of perception” (Ellen Eve Frank) By digging back in the repertoire and shunning convention, Bofill took the work of destruction in order to bring his vision to life. In a sense, it was a sacrifice.

The gravitational pull of the work, the ritualization, the ambiguity and geometric baroqueness of his structures, the use of old styles all gives Bofill’s work a sense of the occult. One project that’s rarely talked about is The Pyramid, an early project built on the highway between his home of Catalan and France, is an earthen mound 80 meters high with a monument on top that against the Pyrenees.

In the Pyramid what was ostensibly a nationalist project took on the form of something out of space or a lost archaeological dig. Some vision, some gesture towards an architecture without purpose, without backing except by divine prerogative, of the gravitational city, the living city of the past/future lies radiating underneath that structure. And as it welcomes people in route to the two ancient countries, a poem of brick remains. It is a testament to the fact that style and tradition are not synonyms, something the occult traditions have always shown.

Maybe Bofill’s work was a glimmer of the true architecture, of poetry made to the scale of society and not just the mind, before it tucked its head back under the Empire. Understandable, in that he wasn’t concerned with complete originality, but not necessarily relatable, and certainly not easily reproduced, his structures offer a swirl of color on top of the void of bottomless, violent modernity and shields against the decayed flames of tradition for tradition’s sake. A place for poets, who carry such gestures in their pockets, saving it for when the ground is ripe for the temples to bloom again.

All photos from https://ricardobofill.com/

Ben, this was a great essay man! I learned a lot.